Answers to questions

It’s a lot easier to look things up these days (thank you Mr Google). Often, instead of taking something for granted, I do some research. It feels good when the pennies drop. Here, I share.

Is colour a recent thing?

Seventy years ago, in 1963, it became possible to see television in colour. After a few years, and when the price of sets had dropped enough to be at the higher end of affordable, the world on TV became more real. But what were things like before that? Were my earlier memories in black and white (as suggested by news media reporting this anniversary)?

Of course not; there was plenty of colour in the world. It’s true that until comparatively recently it was prohibitively expensive to print books in full colour. But there were colour illustrations, printed on separate pages as ‘plates’, and the dust jacket was always in eye-catching colour.

Photography was commonly black and white, but there was colour as well, at least from the late 1930s. Kodachrome slides (1935) were fairly expensive, but very good (Life and National Geographic magazines used nothing else). Movies were all black and white until the 1939 film Wizard of Oz in Technicolor; I remember Disney and Warner Brothers cartoons only in colour.

And earlier? Victorian scraps (for scrapbooks), bunting for royal visits, Christmas parade floats, the circus, advertising posters, vivid flower gardens — there was always lots of colour. Even tinplate toys (German and Japanese), toys made of early plastics or metal (red and green Meccano), and of course the family’s collection of bright Christmas tree orniments. I remember them all. In colour.

What is a knot?

You lookin’ at me???

I’m talking about knots in wood (not rope). Let me explain. I live in a solid wooden house — two storeys of Pinus radiata (Monterey pine), full of knots. Walls and ceilings. Each morning when I wake up I’m looking at two knots arranged above each other so that they could be a very stylised map of our two main islands, complete with weather-map isobars. Others could be eyes. I scare the kids by telling them that the knots are watching them. And that if you look away and then back again, sometimes the knots are in a different place.

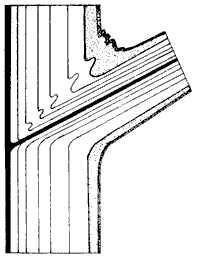

Ok, so what are knots, really? Have a look at the diagram. It’s a vertical cross section of a tree trunk with a branch growing out one side. The lines are the annual growth rings, and you can see how they turn and go sideways where a branch grows out of the trunk. When the trunk is sawn lengthwise into boards, those boards are literally cross sections too. The knots are the branches, seen end-on.

That’s why they’re like the centre part of a trunk sawn straight across. A new lot of branches grows each year, and the sooner in the growing season the tree has been pruned and the branches sawn off, the smaller the knots will be.

Why is news so badly written?

This isn’t an answer to the question, because I really don’t know what the answer is. It’s just a guess as to what the answer might be.

Once upon a time, a journalist would type up a story and submit it to the editor. If it was what the editor wanted, it would go to the subeditor who would mark it up with corrections to grammar and style. Finally, it would be typeset by the compositor, who would query any mistakes he saw while setting the story.

These days, the journalist types the story on a computer. And that’s it. No checks at all. The computer file goes straight into the automated content management system and from there into print and online. It’s up to the reader to try and decipher what the journalist was trying to say.

Some of the results of this new way of doing things are obviously a result of the pressures that result from time constraints and diminished staff. When there’s no time to check, you get errors such as the DomPost telling us on the front page, lead article, first paragraph, that “NZTA” stands for New Zealand Transport Association [should be Agency]. Or Stuff, in an article “Hōrekeke” that a house was built with “…pellets [pallets] down over a dirt floor with second-hand carpet on top.” Errors like these are obviously a result of just not reading through what you’ve written. Others are simple illiteracy, such as the greengrocer’s apostrophe in “…Wellington Water, which looks after stormwater for council‘s in the region…”, or ignorance, such as the times that something is “honed” in on.

But what about the rest? What do you make of an article that tells us in a headline that the “Donkey is down the back” when the article is about a donkey down a bank, or that a burglar rifled through an “undie draw” [drawer]. What about an article discussing old oil and gas wells which says that the country’s abandoned wells will result in “oil and gas coming back to the service [surface]”. Or that power retailers will “sure [shore] up their returns by hedging.” Or that “Wellington is the most expensive main truck [trunk?] airport.”

The most generous way I can interpret these errors is that they’ve been dictated into the computer, and never checked afterwards except for an automatic spelling check. These and many others simply can’t be explained by excusing them as the results of autocorrection by the computer.

Are there any journalists out there prepared to confirm whether that this guess is true or not?

Why do dogs have eyebrows?

I’m not a cat person. People say their cat loves them because it rubs against so affectionately against them. But it will do the same to your chair, or the legs of a table, because it’s just marking its territory. Or they say it’s happy when it’s purring. Well, I’ve experienced an unprovoked bite from a loudly purring cat. They can’t fool me.

Jessie gives me ‘the look’. She was a lovely Sheltie and an important member of our family.

Perhaps a better question would be: how do dogs have eyebrows? With their whole face covered in fur, the eyebrow area isn’t any different to the rest. Yet they do have eyebrows, and they use them for expressions that are almost human.

The secret is the way their face moves. There are muscles above and around the eyes that create the expressions. In fact, dogs have two sets of facial muscles around the eyes that are found in very few other animals. Specifically, only humans, monkeys, apes and (to some extent) horses have these same muscles and are able to have human-like expressions.

Is it because they’re social animals? No. Wolves are very closely related to dogs, and are very social animals that rely on co-operation and communication for success, but they have no eyebrows. There must be another reason, and that seems to be domestication.

If you’ve ever had an intelligent Border Collie look you straight in the eye with a wide-eyed expectant expression, trying to read your thoughts, you’ll understand how dogs became our companions. They have adapted and evolved over the millenia since they shared caves with our early ancestors, in a way that is mutually beneficial. If fact, I often wonder if the difference between animals and humans is just a matter of degree.

What are bugs?

When part of my job was writing ecological leaflets for schoolchildren, and producing simple-English summaries of ecological research, there was one scientific word that I found almost impossible to replace with something simpler. That word was ‘invertebrate’. ‘Creepy-crawly’ was just too kiddywinky, but ‘animals without backbones’ only raised more questions. A list would work if it was short enough, but it was usually too cumbersome. I’m afraid I mostly gave up and just called them invertebrates.

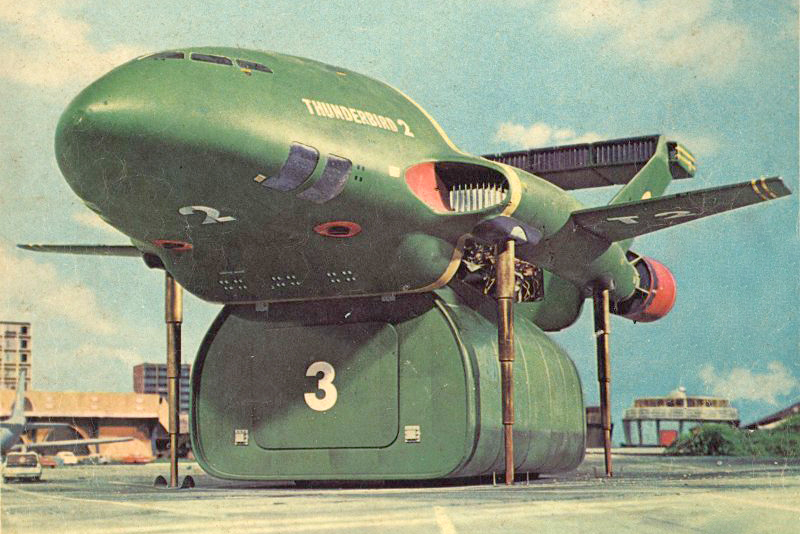

Coincidently, Bug Lab was the work of Richard Taylor’s Weta Workshop

Now there seems to be a partial solution — the word ‘bugs’. Judging by the “Bug Lab” exhibition at Te Papa in Wellington and “Bugs, Our Backyard Heroes” at Puke Ariki in New Plymouth, the term is now used to mean all arthropods, in other words insects, spiders, centipedes and crustaceans (at least terrestrial crustaceans, ie woodlice but not crayfish). At both museums it seems to be a marketing catchword to cover whatever they think people will be interested in. In fact, at Puke Ariki one of the displays is of powelliphantid snails; it just doesn’t matter to the general public, many of whom will be surprised to learn (if they notice) that they aren’t all insects.

As for entomologists — it looks like they’ll just have to give up the term ‘bugs’ and refer to real bugs as hemipterans. And in the field of IT, legend has it that the original computer bug in 1946 was a moth that jammed a relay. It seems a pity that the term ‘moth’ wasn’t used instead. There’s something appealingly descriptive about the idea of moth-eaten software.

Why does wood go darker in colour?

I live in a wooden house. Not a house with a wooden frame, but a Lockwood house — with walls and ceilings of solid pine (Pinus radiata). When newly built the wood was an attractive light buff colour, but now it’s mostly a fairly dark orange. This is typical of Lockwood houses, to the point where new-builds these days use blonded wood to counteract the effect. But why does it happen?

The wood was once a close match to the colour of this plastic button covering a screw head

Varnish on the door frame, showing how it has darkened with age

Varnish on the door frame, showing how it has darkened with age

I used to think that maybe wood just got darker because of the effect of light, or it oxidised, or something like that. Then I noticed that the wood in our house with lightest colour was in areas where it got the most light, particularly window sills on the northern side. Furthermore, I couldn’t see how it could oxidise when it has been covered with a sprayed-on lacquer varnish since it was built.

I remembered a handy model-making trick. Old kits often have decals where the clear layer printed over the image has gone yellow. The trick is to tape the decal sheet up on the inside of a window for a few days so that UV in the sunlight can bleach the yellowed varnish and make the decals usable again. And that’s what I think has happened to our house: the varnish has changed colour.

I had a look around, and I soon found the evidence I needed. By the front door, some varnish had been brushed accidentally onto the door frame. It wasn’t visible originally, but now it shows up clearly as brown brush marks. The varnish is the problem.

Windflow over the cliffs of Kapiti Island

Windflow over the cliffs of Kapiti Island

A real (non-souvenir) kiwi in its nocturnal environment

A real (non-souvenir) kiwi in its nocturnal environment A cute souvenir kiwi (note the nostrils at the wrong end of the bill)

A cute souvenir kiwi (note the nostrils at the wrong end of the bill)